Deadlines Within Deadlines: Cooperative Board Packages and Commitment Letters in NYC Real Estate Closings

A buyer (for purposes of this article, let’s call her Sally Streetwise) works with her broker to find a property she loves in a beautiful cooperative. The brokers work with the buyer and the seller to reach agreement on the key deal points and then turn the delicate deal over to the lawyers to conduct due diligence and to negotiate the more formal contract terms. After much back and forth between lawyers and clients, the contract is finalized, the buyer signs the contract and submits her deposit check, the seller’s attorney deposits the check to an escrow account, and the contract is fully executed.

You might think this would be a great point in time for the brokers, lawyers, buyers and sellers to take a collective sigh of relief, pat themselves on the backs, and look forward to a smooth closing. Alas, there is no rest for the weary in Manhattan real estate. With the finalization of the contract comes something lawyers and brokers deal with every day of their careers, but something first-time buyers like Sally Streetwise may not yet be fully prepared: DEADLINES, and the pitfalls for missing them.

The New York residential real estate contract will not satisfy itself with simply one deadline. There must be multiple deadlines, as many deadlines as there are subway lines (or double-parked cars) in Manhattan: Deadlines to apply for mortgages. Deadlines to obtain Commitment Letters. Deadlines to submit board packages. Deadlines for providing notices. Deadlines to schedule closings. Deadlines to adjourn closings. Deadlines that increase stress and confuse everyone throughout the process. While some lawyers, bankers, and brokers push forward as quickly as possible hoping that they avoid any deadline land mines, experienced practitioners will help the buyer navigate deadlines to lessen their stress and protect their best interests.

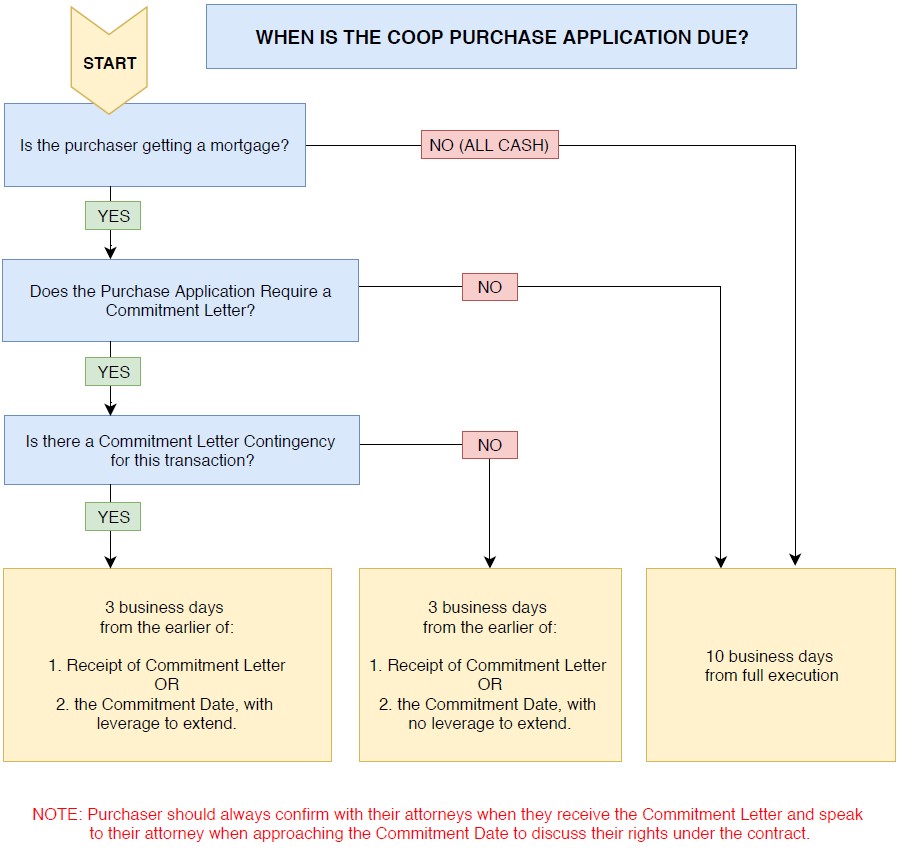

Let’s spend a few minutes to get acquainted with two of the most significant deadlines our buyer will encounter once she gets into contract: the board package submission deadline and the loan Commitment Letter deadline (“Commitment Date”). In the typical contract for the purchase of a cooperative unit, the answer is clear: Sally Streetwise has ten business days to submit her board package. Unless she has three business days. But remember that the three-business-day deadline begins to run at the expiration of a completely different thirty or forty-five-calendar-day Commitment Date. Sometimes. Or it begins to run sooner.

Let’s break that down a little bit further to clear up this confusion. One commonly used contract contains multiple deadlines for the submission of the board package, depending on different circumstances that might exist:

If Sally Streetwise is not seeking financing, and is proceeding “all cash,” she will need to submit her board package within ten business days of her attorney’s receipt of a fully executed contract (unless otherwise negotiated).

If Sally is seeking financing, then the determining factor for the board package deadline will be whether a commitment letter is required to be submitted with her board package. If the board does not require a commitment letter as part of the board package, then the original ten-business-day deadline is still in effect. However, most boards do require a commitment letter because most boards reasonably believe that if a buyer is unable to obtain a commitment letter, the deal will not go forward. There would be no point wasting time reviewing such an application.

If the board requires a commitment letter as part of the board package, then it’s important to note that the contract will include the Commitment Date of usually thirty or forty-five days from the date Sally’s attorney receives a fully executed contract. Sally’s board package deadline also then hinges on whether her contract has a Commitment Letter contingency.

If Sally’s contract has a Commitment Letter contingency, then her deadline is three business days from the earlier of when she receives the Commitment Letter or the Commitment Date.

If, on the other hand, Sally is seeking financing but her transaction does not include a Commitment Letter contingency, then Sally’s deadline is three business days from the earlier of: (1) when she receives the Commitment Letter or (2) the Commitment Date, with one important caveat: even if Sally has not obtained a Commitment Letter by the Commitment Date, she must still submit her board package within three business days from the Commitment Date.

Given the complexity described above, we would always recommend that a potential buyer, with the assistance of her broker, obtain a copy of the board application before entering into the contract for the purchase of the cooperative unit. This way they will know ahead of time whether the board requires the commitment letter as part of the board package and thus the deadline to submit that package. The broker and the buyer should work together to get the board package as complete as possible so that the only open item remaining while approaching the Commitment Date will be the lender’s issuance of a Commitment Letter.

One common pitfall to note: we all come across deadlines in our daily lives. When facing a deadline, there’s often an impulse to hurry up and beat the deadline by as many days as you can. In the context of the Commitment Date described above, and board package deadline, however, this is not necessarily the best path forward.

Once parties are in contract, Sally Streetwise should start working on her loan with her banker and on the board package with her broker. The goal for both is not necessarily to beat the deadlines to a pulp, but rather to meet the deadlines with the best work product possible within the time permitted.

For bankers working on the commitment letter, a number of open conditions may initially exist on the commitment letter and the banker should work with the client to try to eliminate as many open conditions as possible prior to the Commitment Date. For example, if a banker states that Sally Streetwise’s parents must provide a “gift letter” for funds that were given to her to purchase her first home, it would be best to obtain the gift letter and have that condition cleared from the commitment letter, rather than having the commitment letter issued with the open condition. What if Sally’s parents refuse to sign a “gift letter” for the funds they provided her? These types of potential issues would be better discovered while in the contingency period rather than after the contingency has lapsed.

It is also critical to have an experienced banker who is familiar with the interplay of the Commitment Date and the board package timeframes. Less experienced bankers may issue a commitment letter quickly in an apparent effort to impress the borrower, but inadvertently trigger the 3-day deadline described above when the borrower is not yet ready to submit the board package.

With respect to the board package, Sally Streetwise will want to have an open dialogue with both her banker and her broker, so that they take the time to prepare a board package that shows Sally in the best light and is most likely to result in board approval. Sometimes this means waiting until the most recent bank statements are available from the buyer’s bank, or waiting until the perfect source of a professional reference is back from vacation.

There is one notable exception to the above. What should Sally do when she obtains a commitment letter that is still subject to a satisfactory appraisal, but the appraisal has not yet been conducted or approved by the bank? In such a case, the typical real estate contract states that a commitment letter subject to an appraisal is not a “Commitment Letter” as defined in the contract unless and until the appraisal condition is satisfied. The first goal would be to make sure the appraisal is satisfied before sending the Commitment Letter as part of the board package. However, there are times that the broker will want to submit the board package quickly, for example to make the next board meeting deadline, and so they would prefer to submit the commitment letter with the appraisal condition. In such a case, the buyer may decide to submit the commitment letter even though it is still subject to an appraisal, but the buyer should state that it is a preliminary commitment letter with their right to cancel still intact under the standard commitment letter contingency clause.

One final note on deadline extensions: buyers should take note that in the world of contract law, there is a difference between a deadline where a buyer is given a right of action and a deadline where a buyer has no such right. For example, take the case where a buyer with a finance contingency has done her best to cooperate with the bank to obtain a commitment letter, but through no fault of her own, the bank is unable to issue the commitment letter prior to the typical thirty-day deadline. In such a case, the buyer would potentially have the right to cancel the contract. Given that right, there is a possibility that a buyer could request from the seller an extension of that deadline rather exercising the right of cancellation. This wielding of the implied power to cancel often results in the seller granting an extension.

Contrast this situation with the deadline to submit a board package. Here, in the normal circumstance, the buyer does not have a right to cancel if the board package is not submitted on time, and therefore may not be successful in seeking an extension of such a time. Seeking an extension in such a circumstance comes with risk. If the seller does not agree (and there is no requirement that they do) then the buyer must rush to submit the board package or risk being held in breach of the contract, which potentially subjects the buyer to the loss of the deposit. If a broker or client is concerned with the board package submission deadline, the most effective time to address this concern is during the contract negotiation stage, when additional time can be added to the contract.

Due to the complex interplay of deadlines described herein, it is imperative that a buyer work with seasoned professionals when selecting a lawyer, broker, and banker. Each of these professionals works with the others to ensure that the deadlines are effectively met and with information that puts the buyer in the best possible position to succeed in the transaction.

PLEASE NOTE: This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute the dissemination of legal advice. The deadlines and some of the legal language discussed herein is subject to negotiation between the parties involved and/or interpretation by a court of law. We encourage you to speak with the attorney handling your specific transaction for further details.

5 Things to Consider When Choosing a NYC Real Estate Attorney

When buying or selling a property, a knowledgeable lawyer that practices Real Estate law will help make sure you get exactly what you want out of the transaction.

1. Knowledge of New York City Residential Transactions

The “Concrete Jungle” has a unique housing stock unlike anywhere else in the U.S. For example, the great majority of Co-ops that exist in the U.S. are in New York City. Because of these unique features, there are intricacies to closing a NYC Real Estate Transaction that a well-qualified attorney can help to explain. These include things like knowledge of local regulations, understanding the custom and practices in cooperative, condominium and house purchases, experience dealing with the New York City network of brokers. Additionally, it is preferable to have an attorney who has completed sales in the building, or similar buildings, that you plan to buy/sell in. Knowledge in the field means knowing what to look for to ensure the transaction goes as smoothly as possible.

2. Personalized Attention

You do not want a Real Estate Attorney who takes a cookie cutter approach to one of the most important transactions of your life. A good real estate attorney will give you personalized attention and be available to answer the questions you have when they come up. To achieve this, it is important to have a team of individuals working on your transaction, rather than just one person. Extra sets of eyes ensure that details are not overlooked.

Also, you want to make sure that an attorney is working on your transaction, not just a paralegal or an administrative assistant. Some firms assign only a paralegal to the transaction, a practice we do not employ. Many times we have two attorneys working on one transaction, both for a smooth client experience and to allocate resources where they are most needed.

Like a doctor with good bedside manner, a good attorney will form a close bond with their client that is based on mutual respect and trust. Despite all the lawyer jokes you may have heard, most attorneys are hard-working, excellence driven, respectful individuals who are trying to do their best for their clients. Our firm puts a focus on this aspect of the relationship because we feel it is the centerpiece of the real estate transaction puzzle.

3. Fees

Fees will vary depending on the size and complexity of a transaction. They will generally be structured as a flat fee, with half payable up front and the balance payable after closing. Factors that affect the fee, include but are not limited to: (1) whether the purchase will be made in cash or require a mortgage; (2) if there is a lender, whether it is an institutional or a private lender; (3) whether the transaction involves Federal or State tax withholdings; (4) whether the client will be able to attend the closing; (5) whether there are any anticipated title issues; (6) whether the transaction includes anything that is not part of the normal process of buying or selling a property in NYC.

Some firms will refer to all or a portion of the fee as “non-refundable.” We do not agree with this approach and will refund any unused portion of the retainer on any transaction. Other firms will say “no fee if we do not get you to the closing.” We do not agree with this approach either, as we feel it will create a conflict of interest where the attorney may unconsciously rush to conclude a transaction or hold back emphasis on any issues that arise that might jeopardize the transaction in any way.

See an article on the firm’s origin and philosophy here.

4. Provide Consultation and Guidance on all Aspects of the Transactions

A good real estate attorney will advise you on all of the risks associated with the transaction and guide you on how to proceed. They will advise you, not only on the legal aspects of the transaction, but also help you to identify and manage the wide assortment of risks that affect the viability of a residential transaction. This includes reviewing board minutes, building financials, the offering plan, and other important documents. In addition, an attorney will help you coordinate a loan commitment, negotiate a contract for a sale and much more.

A good attorney will also know how to allow a client to be a valuable resource as well. Even if a client knows nothing about real estate or financing, they can still provide key information about the condition of the property, what it looks like, what they expect to receive, and what their most important needs are from the property. A good attorney will know when to ask questions and when to provide answers, while a not-so-good attorney thinks they know all the answers and never asks a single question.

5. Team Player with Proven Track Record

It is important to choose an attorney who is empathetic to your needs, works well with others, and has a proven track record supported by professional referrals. Ultimately, choosing an attorney is a very personal process. Check out information on our firm here!

Helpful Resources for Purchasers

Though we navigate it every day, the Due Diligence process can often appear opaque or overwhelming to new buyers. The City, State, and Federal governments host a number of helpful resources, but these can be difficult to find for those who do not know where to look.

To that end, we have compiled a list of online resources where relevant information can be freely accessed, such as property records, tax information, and payment portals for municipal services, among others. We hope that they can be of use not only to prospective purchasers, but to current homeowners as well.

Please note that web addresses can change over time. If a link is broken, we recommend working backward through the URL to the last intact page.

NYC Housing Mysteries: What is an I-Card?

The I-Card is a paper record that the City of New York adopted in 1902 to document the required building improvements of tenements and multiple dwelling buildings, and for regulating their use. It was a product of the Progressive Era, a period around the turn of the last century when building codes, sanitary conditions, and safety issues in tenement housing all came under greater scrutiny.

Thus, the city came up with a way to track the required alterations that certain buildings made over time—the “I” in “I-Card” refers to these improvements. Such regulations demanded that a tenement had proper and adequate fire-escapes and means of egress through the roof, as well as proper ventilation and lighting in interior areas.

Following the new legislation, the Tenement Housing Department had to locate and review all 83,000 tenements within the city. The department thus developed a standard means of inspection that could be learned quickly by their employees and filed so that these cards could be accessed readily for future inspections. These cards also contained drawings or diagrams to show the exterior and interior arrangement of each tenement house.

For buildings without a Certificate of Occupancy, which was not required until circa 1938, the I-Card can be accepted as the legal record of existing occupancy as of the last date indicated on the card. However, buildings with I-Cards may have or need more recent legal occupancy records if any lawful alteration or conversion work was performed in the building beyond that date. Not all houses built before 1938 have I-Cards—this is likely because they were misfiled, lost, or inadvertently destroyed—but if a building was never considered multiple-dwelling (i.e. housing three families or more) or inspected as such, then it would never have acquired an I-Card in the first place.

Sources:

https://hpdonline.hpdnyc.org

A Beginner’s Guide to the 421 Tax Abatement

What is it And Who Qualifies?

The 421-a tax abatement was created in 1971 to encourage the development of underutilized or unused land by significantly reducing property taxes on newly developed land for a set period of time.

During the time period, thousands of New Yorkers were moving upstate or to the suburbs, and City officials feared a decline in residential development. Initially the city gave these tax breaks to any newly constructed development, but as the Manhattan housing market rebounded in 1980’s, the City created an “exclusion zone” between 14th and 96th Streets. Any developers building in this “exclusion zone” were 421-a eligible only if they constructed affordable housing on-site (typically 80/20, with 20% being low-income units) or off-site (by purchasing certificates that were used to create low-income units in other parts of the city).

Thousands of condominiums across Manhattan were developed under this program prior to the 2008 housing market crash. The abatement was available for new developments located only on lots that were vacant, underutilized, or “nonconforming” with the prescribed zoning use under the 421-a abatement. Owners are exempt from paying any increases in property taxes that result from new construction. The 421-a abatement was initially set to run for 10 years, but can run for as long as 15-25 years in upper Manhattan and the outer NYC boroughs.

The 10-year abatement provides unit owners with a 100% abatement from property tax increases for the first two years, with taxes then being increased by 20% of the current tax rate every two years for the remaining eight years. For example, if an apartment is bought in a building that had a 421-a abatement in the first year and sold in the seventh year, the new buyer would have the remaining three years of reduced taxes, since the abatement stays with the property and does not follow the owner.

This tax abatement expired in January 2016, due to disputes over wages between the construction industry and developers. However, a revival bill dubbed 421-a, “Affordable New York,” is currently being developed in the state Legislature. The “Affordable New York” bill would permit qualified developers a 100% property tax break for a term of 35-years, mandating that all affordable units remain so for a 40-year term. The bill also includes mandates regarding construction worker wages and benefits. The newest version of the bill suggests allowing outer borough developments with up to 80 units to qualify (an increase from the 35 units necessary to qualify in the Governor’s initial proposal).

Currently, the biggest issue is the debate over the average assessment value for qualifying condominiums, with NY Republicans looking to raise the limit from $65,000 to $85,000. By increasing the assessed value (which is based on a percentage of the unit’s market value), pricier properties will then qualify for the abatement. This has led many to question whether the 421-a program actually promotes affordable housing, or if it just incentivizes private development in the outer boroughs. It does not help that affordable housing benchmarks have been hit in the time since expiration, and the anticipated cost to the City to support the program with the current proposals are expected to total $1 billion (estimated at $100-120 million per year) over a ten-year period, seemingly while not increasing the affordable housing inventory.

Mayor De Blasio and Governor Cuomo have fought publicly after the former introduced a proposal that would expand affordable housing, which the Governor shut down because of inadequate pay for construction personnel. The Mayor has described the current proposals as an “undue burden” on NYC residents, with the cost for each affordable unit increasing to $592,000 from $507,000 when the initial version of 421-a was in effect.

Things to Consider Despite Tax Relief Opportunities

When buying a condominium or co-op, it is important to consider the scenarios in which these tax abatements fall off or change, and to research which new laws or regulations have potential impact on your purchase in the next 3-5 years. What will be the real cost when the abatement expires? The property taxes could drastically jump to levels higher than those at the time of purchase.

Some Useful Links For Buyers and Sellers

Are you having a hard time finding resources on Real Estate subjects? We recently compiled a list of useful links for those looking to learn more about real estate processes, laws, and taxes. It includes both municipal resources and other helpful sites, such as Streeteasy and Oasis, a source for detailed community maps. We hope that they can be of use to you!

From the NY Times: What to Expect when You’re Closing

The closing is the climactic moment in a Real Estate transaction, when the deal is finalized and the money finally changes hands. However, the big moment can be daunting, especially in New York, where the large cast of characters can include not just the seller, purchaser, and their attorneys, but possibly several brokers, a lender, the lender’s counsel, a management company, and title company as well. But what really goes on, and what should a prospective buyer or seller prepare for to make sure that the final step goes smoothly? This article, originally published in the New York Times, offers a helpful guide for first-timers.

What are HDFC Buildings?

HDFCs (Housing Development Fund Corporations) are essentially income-restricted cooperatives; they limit a potential purchaser’s ability to buy in based on whether their annual salary falls below the calculated income cap. The establishment of HDFCs were geared toward purchasers looking for a residential home to keep for a substantial period of time, with the possibility of passing it on to family members. They compose much of New York City’s affordable housing. HDFCs are further classified by the way in which the low income cap is calculated, either through a regulatory agreement with the city or without one.

If the building does have a regulatory agreement, then the income cap is based on a percentage of the median income within the surrounding neighborhood. If the building does not have a regulatory agreement, then the income cap is generated by a formula based on the building’s maintenance charges and utilities fees. Usually, the standard is to bracket the income at about seven times the annual maintenance charge. Further, the income cap will mimic the economics of the surrounding area and increase when the area becomes more affluent. For instance, as a maintenance charge increases within an HDFC building, the income cap will follow suit and allow for a greater annual salary. While HDFCs require a purchaser to fall within the low income cap, there is no requirement as per the resale price. Thus, a seller has full discretion in determining the market price of the HDFC. Nonetheless, the resale price is often regulated by the high flip tax that HDFC buildings impose (often about 30% of the profit) and the relatively limited supply of potential buyers that fit the income requirements to purchase.

The HDFC market is aimed to benefit purchasers, since a potential purchaser is able to acquire a high-profile residence at a price that is substantially lower than the market rate. The ideal purchaser is someone that has acquired a large trust or inheritance but has a low income. However, a purchaser trying to obtain funding may run into issues as banks tend to look less favorably on HDFC loans. This arises from the fact that HDFCs are seen as riskier investments, and thus have higher rates. Moreover, where a purchaser is unable to obtain bank financing, the HDFC is likely to require an all cash transaction. We would urge any HDFC purchasers to consult with a banker that has a proven track record of closing loans on HDFC projects, as the financing component of the transaction is often the piece of the transaction that has the most associated risk.

For further information on HDFCs please check out the following links:

Understanding Contracts: the Statute of Frauds

Contracts are at the heart of buying and selling real estate. This is because, by law, no real property can legally change hands (with the exception of a lease lasting less than one year) except through a written contract. This law is called the “Statute of Frauds.”

In order to be legally binding, a contract must contain certain basic information. First, it must explicitly name the parties involved in the deal. Failure to do this may make the contract impossible to enforce. Secondly, the specific boundaries of the subject property must be listed accurately, and with enough exactitude as to be easily identified. “By the long rock wall with a big oak tree at the north end,” unfortunately isn’t sufficient for the contract to be binding. Third, the purchase price for the property in question must also be listed and decided upon before the contract is signed, not after. Depending on the contract, it may also need to include such facts as closing date, the terms of the mortgage (if applicable), and information about the title of the property (amongst others).

Provided that a contract has all of the necessary information, the form that the contract takes contains a great deal of leeway. The contract could be many documents pieced together, some terms legibly scribbled on a napkin, or even an email chain (provided, of course, that they are sufficiently connected and that the required signatures can be proven genuine—a subject of no small amount of controversy). There is even one exception to the Statute of Frauds: in some cases an oral recitation of the contract may pass muster, provided that is obvious that all parties’ actions explicitly refer to the deal.

Hopefully, this tidbit of legal theory will help put the contract process into context. With any more specific questions, we would always recommend contacting a legal professional.

A Beginner’s Guide to Condops

A condop is a co-op governed by condominium rules, right? Not quite. Colloquially, “condop” often refers to a co-op that claims to have a lenient board and subsequently operates more like a condominium, but this definition is not actually correct.

In a hybrid condominium-co-op, also known as a “condop,” the building or property is divided into a multi-unit condominium, usually with separate commercial and residential units. For example, in a twenty-story high-rise building, the commercial space on the ground floor may be one condominium unit while the remaining nineteen floors containing multiple residential coop units are considered to be a second, separate condominium unit. The residential unit portion is thereby operated by a co-op corporation, while the commercial unit or units can be retained or sold by the developer.

The portion of the building that comprises the residential condo unit is broken up into small residential co-op units and ownership is largely the same as a typical co-op. Each purchaser executes a subscription agreement to purchase stock in the corporation, and each purchaser is considered to be a tenant-shareholder of the corporation that owns the residential condo unit. Unlike a regular co-op, however, the co-op corporation in a condop owns the residential condo unit rather than fee title to the entire building. The co-op corporation that owns the residential condo unit and the owner of the commercial condo unit would operate the two-unit condominium building that makes up the entire property in accordance with the condominium rules.

It is important for prospective purchasers to know the difference between a condop and a co-op or a condominium building because of the due diligence involved when looking into investing in such property. While one may look solely at the financial information for the condominium as a whole, in a condop, it is necessary to also review the financials of the co-op to determine the financial health of the investment. And it is important to note that a condop will not necessarily have a more lenient board, though this is sometimes the case.

Hopefully this clears up some of the many misconceptions that surround condops. Overall, it is important for any prospective buyer or investor to have a thorough understanding of the rules and policies of any building they hope to deal with, regardless of its label.

Sources:

Vivian S. Toy, What Exactly is a Condop?, N.Y. TIMES, May 20, 2007